Katarina 'Kat' Almeida-Warren

Research Affiliate

School of Anthropology and Museum Ethnography, University of Oxford

Biography

I am a primate archaeologist with a background in archaeology, primatology, and anthropology. I am interested in the archaeology of non-human primate tool-use and culture, with a focus on its exciting contributions to human origins research. My expertise spans chimpanzee plant technology (termite-fishing), stone technology (nut-cracking), and the formation of technological landscapes, using a range of archaeological and primatological approaches including raw material studies, landscape archaeology, behavioural ecology, and agent-based modelling.

Since 2022 I have been leading the very first investigation into the archaeology of non-technological chimpanzee behaviours, Primate Archaeology Beyond Technology: Delving Deeper into our Primate Heritage, providing the first glimpse of what is yet to be unearthed from our distant past.

Recently, I have also started applying my knowledge in primate conservation, particularly helping to develop pathways for integrating the culture concept into conservation practice. I have also been building expertise in science education and outreach, working with GLAM partners and developing engaging hands-on activities linked to chimpanzee culture and conservation.

Do get in touch if you would like to discuss ideas or potential collaborations in reseach and/or outreach!

- Primate archaeology

- Primate cultures & technology

- Primate ecology

- Human origins

- Conservation

- Heritage

- Agent-based modelling

PhD in Anthropology, 2022

University of Oxford

MSc in Human Evolution and Behaviour, 2015

University College London

BSc in Archaeological Sciences, 2013

University of Sheffield

Current affiliations

Research

Recent & Upcoming Talks

Featured Publications

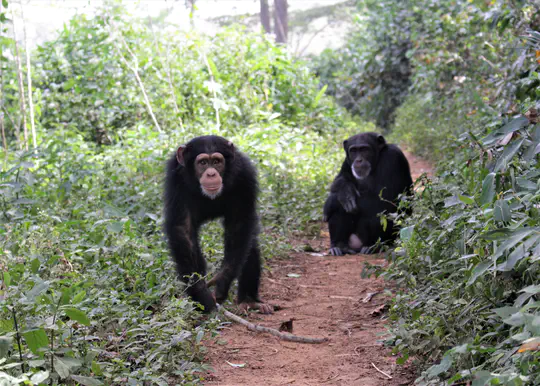

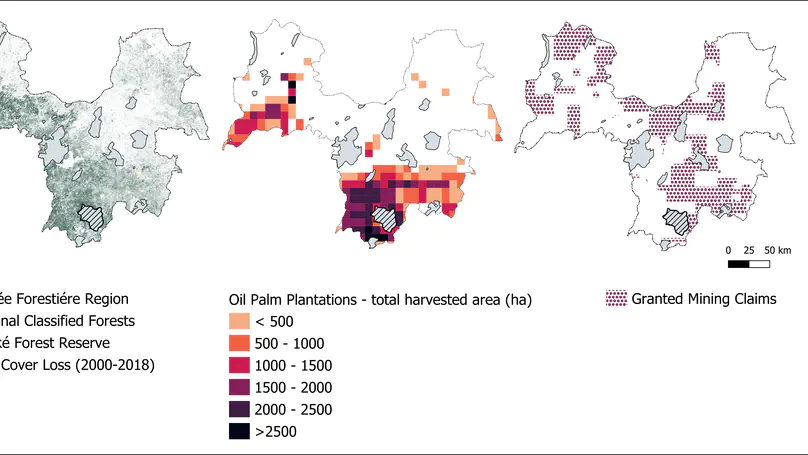

The Diécké Forest is the second largest classified forest in Guinea and is an area of high conservation significance for many species including the western chimpanzee, Pan troglodytes verus. It has attracted several research expeditions focusing on chimpanzee presence and tool use since 1993. These studies also identified several instances of human activities impacting primates and other wildlife. Aside from Bossou, Diécké is the only other locality in Guinea where chimpanzees are known to crack nuts with tools. We visited the Diécké Forest in November 2018 to review the status of chimpanzee presence, nut-cracking activity, and conservation threats. We report our findings along with an up-to-date overview of relevant historical, sociopolitical, environmental, and scientific developments in the vicinity. Our survey took place in the vicinity of Korohouan village where research on chimpanzee nut-cracking had previously been conducted. We found scarce evidence of chimpanzee presence in the area (n = 3) with no recent traces of nut-cracking or other activities. Conversely, we found a high incidence of hunting (6.31/km) within the protected area, with smallscale agriculture and commercial activities predominating forest fragments outside the protected area. The intensification of human activities in Diécké pose a serious threat to one of the largest remaining lowland evergreen forests of West Africa and the endangered species that inhabit it, such as the Western chimpanzee. Our study highlights the need for urgent and concerted conservation action and provides an important case study on the disappearing cultural heritage of a chimpanzee population in a human-impacted habitat.

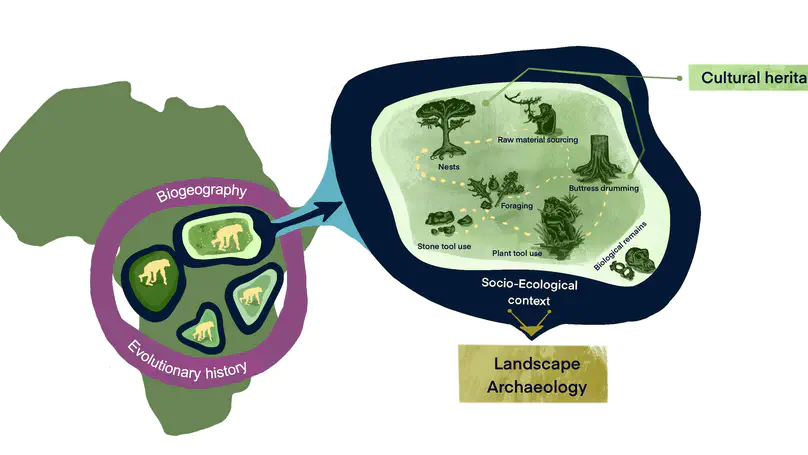

The new field of primate archaeology investigates the technological behavior and material record of nonhuman primates, providing valuable comparative data on our understanding of human technological evolution. Yet, paralleling hominin archaeology, the field is largely biased toward the analysis of lithic artifacts. While valuable comparative data have been gained through an examination of extant nonhuman primate tool use and its archaeological record, focusing on this one single aspect provides limited insights. It is therefore necessary to explore to what extent other non-technological activities, such as non-tool aided feeding, traveling, social behaviors or ritual displays, leave traces that could be detected in the archaeological record. Here we propose four new areas of investigation which we believe have been largely overlooked by primate archaeology and that are crucial to uncovering the full archaeological potential of the primate behavioral repertoire, including that of our own: (1) Plant technology; (2) Archaeology beyond technology; (3) Landscape archaeology; and (4) Primate cultural heritage. We discuss each theme in the context of the latest developments and challenges, as well as propose future directions. Developing a more “inclusive” primate archaeology will not only benefit the study of primate evolution in its own right but will aid conservation efforts by increasing our understanding of changes in primate-environment interactions over time.

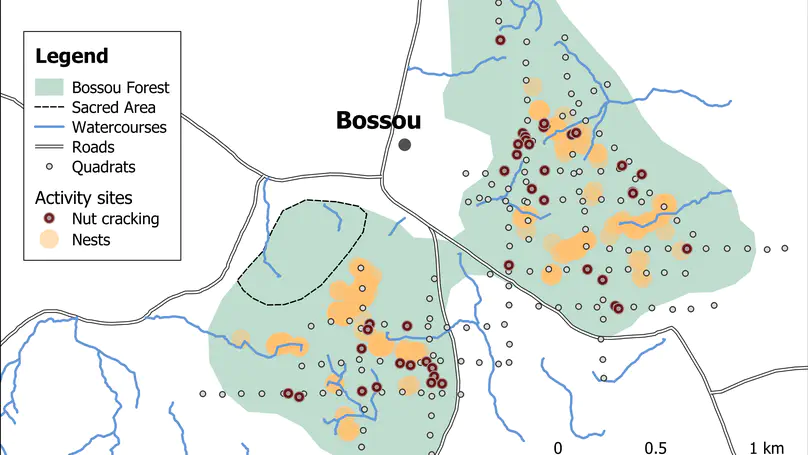

Ecology is fundamental in the development, transmission, and perpetuity of primate technology. Previous studies on tool site selection have addressed the relevance of targeted resources and raw materials for tools, but few have considered the broader foraging landscape. In this landscape-scale study of the ecological contexts of wild chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes verus) tool use, we investigated the conditions required for nut-cracking to occur and persist in discrete locations at the long-term field site of Bossou, Guinea. We examined this at three levels: selection, frequency of use, and inactivity. We collected data on plant foods, nut trees, and raw materials using transect and quadrat methods, and conducted forest-wide surveys to map the location of nests and watercourses. We analysed data at the quadrat level (n = 82) using generalised linear models and descriptive statistics. We found that, further to the presence of a nut tree and availability of raw materials, abundance of food-providing trees as well as proximity to nest sites were significant predictors of nut-cracking occurrence. This suggests that the spatial distribution of nut-cracking sites is mediated by the broader behavioural landscape and is influenced by non-extractive foraging of perennial resources and non-foraging activities. Additionally, the number of functional tools was greater at sites with higher nut-cracking frequency, and was negatively correlated with site inactivity. Our research indicates that the technological landscape of Bossou chimpanzees shares affinities with the ‘favoured places’ model of hominin site formation, providing a comparative framework for reconstructing landscape-scale patterns of ancient human behaviour. A French translation of this abstract is provided in the electronic supplementary information: EMS 2.

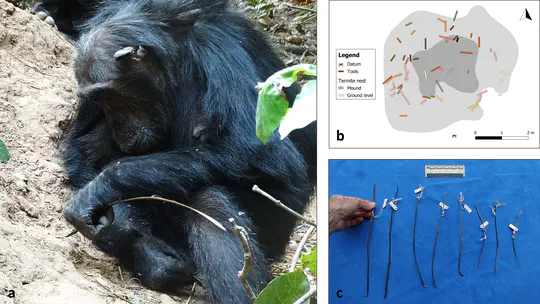

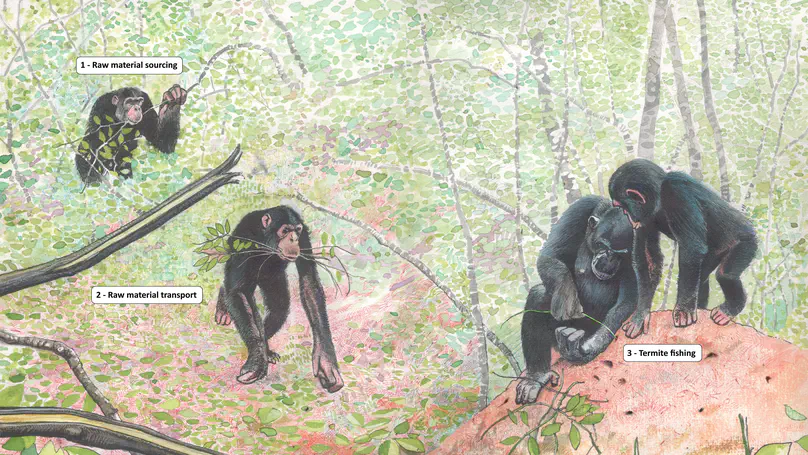

Selection and transport of materials for tools is ubiquitous throughout our species’ evolutionary history. Yet our understanding of early human material culture is heavily skewed toward lithic technology. This poses challenges when reconstructing our technical origins, as organic raw materials, especially plants, likely played a significant role despite their absence from the record until 300 kya. Studies of plant-tool use by living apes can serve as a proxy to reconstruct such aspects of human behavior. Employing archaeological methods, we investigated raw material procurement for termite-fishing tools by three chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes schweinfurthii) populations in Tanzania: Gombe, Issa, and Mahale. All communities exploited plant sources from the immediate vicinity of termite mounds, as well as farther away, and reused them. However, at Issa, more parts were sourced per plant, with the number of removals decreasing as distance from the mound increased. These disparities are likely caused by environmental differences. Issa apes might try to minimize transport costs in what is a comparably more open and drier habitat with fewer suitable sources available near mounds. Despite similar raw material types being available, Issa and Mahale chimpanzees exclusively used bark for tool manufacture, while at Gombe, various materials were employed; these differences may reflect cultural variants. Our study highlights how environmental and cultural factors shape chimpanzee technology and identifies similarities to raw material selection processes inferred for Oldowan tool users. The archaeology of the perishable, even if at its infancy, is providing a new framework for reconstructing archaeologically invisible aspects of early human behavior and our own technological origins. Online enhancements: supplemental tables.