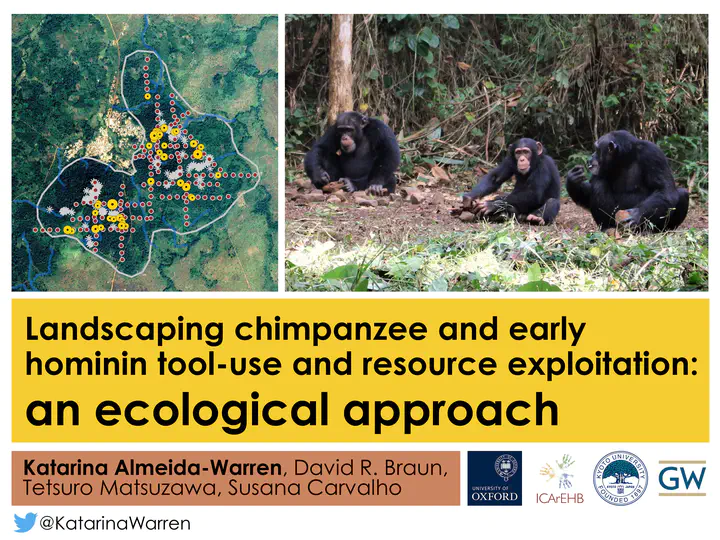

Landscaping chimpanzee and early hominin tool-use and resource exploitation – an ecological approach

Image credit: K. Almeida-Warren

Image credit: K. Almeida-WarrenAbstract

Ecology plays an important role in the emergence and maintenance of technological traditions in non-human primates, and shapes their tool-using behaviours (Koops et al. 2013; 2014; Carvalho et al. 2011, 2007; Rolian & Carvalho 2017). For example, raw material availability and proximity to water, influence site location and re-use, as well as frequency and distance of tool transport in chimpanzee nut-cracking (Carvalho et al. 2011, 2008). Such features may have also determined early hominin resource exploitation strategies and the distribution of archaeological assemblages, particularly before the emergence of more permanent ‘home bases’ (e.g. Isaac 1981; Rose & Marshall 1996; Sept 2011). However, due to the sparsity of the earliest records and the absence of comparative frameworks, few studies have successfully tested these hypotheses. Our closest living relative, the chimpanzee, is a universal tool-user and provides key insights into the behaviour of our ancestors. Chimpanzee tool-activity areas bear similarities to low-density assemblages of early hominins, probably due to similar forage-on-the-go strategies (Carvalho & McGrew 2012; Thompson et al. in press, 2019). This provides a unique window for testing the mechanisms driving accumulation patterns across the landscape, using extant and extinct species. We develop the first standardized method of data collection for modern chimpanzee and early hominin sites and investigate which ecological variables drive the selection and re-use of nut-cracking locations by the chimpanzees of Bossou (Guinea). First results suggest that, after nut tree availability, access to raw materials and predictable resources (e.g. fruiting trees), are the main parameters explaining variability in nut-cracking assemblages, while proximity to sleeping sites is non-significant (random forest model: ntree = 500, nper = 999; variance explained = 26.33%; p < 0.05). Ongoing comparisons with data from Koobi Fora (Kenya), will further test key models of landscape-use and provide a clearer picture of early hominin resource exploitation.